What’s your contribution in spreading the importance of antimicrobial resistance?

I believe it’s vital to include more antibiotic resistance content in medical education. I regularly lead webinars and training sessions for doctors as part of their ongoing professional development and accreditation, providing them with up-to-date, structured information.

I also see value in organizing on-site training in hospitals near the war zone. This allows direct observation of infection control challenges, which can differ greatly between hospitals and impact the spread of antibiotic resistance.

You are a good communicator. What is most effective way to reach the professionals about antibiotic resistance?

Effective learning happens when information is engaging and memorable, not just passively received. That’s why sessions should be delivered by dynamic speakers, with structured, clear content to keep participants engaged.

I also support a peer-to-peer model, where trained doctors can then educate their colleagues locally. This approach strengthens both learning and long-term knowledge sharing.

“I believe it’s vital to include more antibiotic resistance content in medical education”

It’s important to reach the population. What is the most effective way to do it?

Awareness about antibiotics should begin early, starting in school. Simple concepts—like what bacteria are, the role of vaccines, and why not all illnesses need antibiotics—can be taught from grades 6–7. This helps prevent future misuse, such as self-medicating or thinking antibiotics cure everything.

The public needs to understand that antibiotics only target specific bacteria and are not for fever, diarrhea, or wound healing.

How to engage with representatives of the government?

Communication with the government often happen through committee experts made by working groups that include professors, researchers, and practicing doctors.

The key question is how these experts are selected to join such groups—something I haven’t sort it out yet. All the bureaucratic processes, regulatory documents, recommendations and orders are usually developed by these working groups.

“Effective learning happens when information is engaging and memorable, not just passively received”

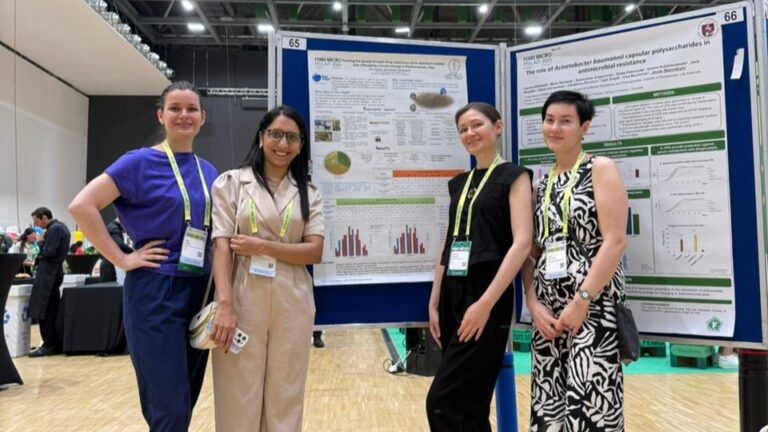

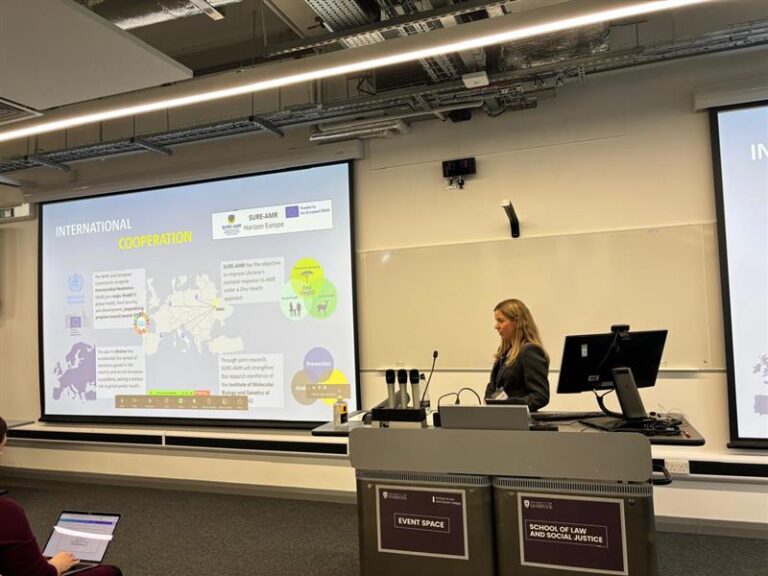

Why is SURE-AMR important for Ukraine?

In Ukraine communication is lacking between individuals, hospitals, and authorities, especially among scientists, clinicians, and those issuing regulatory documents. I am hopeful about this project as it aims to bridge these gaps by fostering collaboration, sharing crucial data, and promoting coordinated actions to tackle antibiotic resistance more effectively.

What is your opinion of having the opportunity to be part of this project?

As a practicing bacteriologist, I find it very valuable to interact with European colleagues, see how their laboratories are set up, learn to use their equipment and methodologies, especially since our labs are mostly modestly equipped and many still work manually. That’s why expanding my technical horizons is so important to me and something I’m truly grateful for.

How do you see the outcomes of this project for IMBG?

I see IMBG becoming a modern research centre for antibiotic resistance — a centre that engages with many partners, and one that anyone can turn to with any question on the subject. I hope IMBG becomes a centre where anyone can find a specialist capable of providing a qualified answer about antibiotic resistance. I believe this would be the best possible result we can expect from SURE-AMR.